Back تناقص الجليد البحري في القطب الشمالي Arabic Malpliiĝo de la arkta glacitavolo Esperanto Disminución del hielo marino ártico Spanish کاهش دریایخ شمالگان Persian Penyusutan es Arktik ID Declino del ghiaccio marino artico Italian Пад на морскиот мраз на Арктикот Macedonian Sự suy giảm băng biển Bắc Cực Vietnamese 北冰洋海冰縮水 ZH-YUE

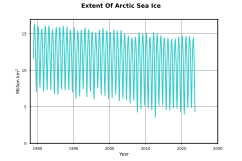

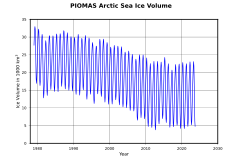

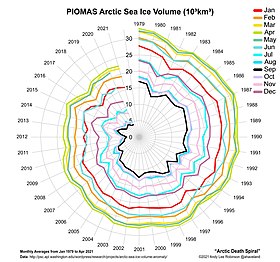

Sea ice in the Arctic region has declined in recent decades in area and volume due to climate change. It has been melting more in summer than it refreezes in winter. Global warming, caused by greenhouse gas forcing is responsible for the decline in Arctic sea ice. The decline of sea ice in the Arctic has been accelerating during the early twenty‐first century, with a decline rate of 4.7% per decade (it has declined over 50% since the first satellite records).[1][2][3] It is also thought that summertime sea ice will cease to exist sometime during the 21st century.[4]

The region is at its warmest in at least 4,000 years[5] and the Arctic-wide melt season has lengthened at a rate of five days per decade (from 1979 to 2013), dominated by a later autumn freeze-up.[6] The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (2021) stated that Arctic sea ice area will likely drop below 1 million km2 in at least some Septembers before 2050.[7] In September 2020, the US National Snow and Ice Data Center reported that the Arctic sea ice in 2020 had melted to an extent of 3.74 million km2, its second-smallest extent since records began in 1979.[8] Earth lost 28 trillion tonnes of ice between 1994 and 2017, with Arctic sea ice accounting for 7.6 trillion tonnes of this loss. The rate of ice loss has risen by 57% since the 1990s.[9]

Sea ice loss is one of the main drivers of Arctic amplification, the phenomenon that the Arctic warms faster than the rest of the world under climate change. It is hypothesized that sea ice decline also makes the jet stream weaker, which would cause more persistent and extreme weather in mid-latitudes.[10][11] Shipping is more often possible in the Arctic now, and expected to increase further. Both the disappearance of sea ice and the resulting possibility of more human activity in the Arctic Ocean pose a risk to local wildlife such as polar bears.

One important aspect in understanding sea ice decline is the Arctic dipole anomaly. This phenomenon appears to have slowed down the overall loss of sea ice between 2007 and 2021, but such a trend is not expected to continue.[12][13]

- ^ Huang, Yiyi; Dong, Xiquan; Bailey, David A.; Holland, Marika M.; Xi, Baike; DuVivier, Alice K.; Kay, Jennifer E.; Landrum, Laura L.; Deng, Yi (2019-06-19). "Thicker Clouds and Accelerated Arctic Sea Ice Decline: The Atmosphere-Sea Ice Interactions in Spring". Geophysical Research Letters. 46 (12): 6980–6989. Bibcode:2019GeoRL..46.6980H. doi:10.1029/2019gl082791. hdl:10150/634665. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 189968828.

- ^ Senftleben, Daniel; Lauer, Axel; Karpechko, Alexey (2020-02-15). "Constraining Uncertainties in CMIP5 Projections of September Arctic Sea Ice Extent with Observations". Journal of Climate. 33 (4): 1487–1503. Bibcode:2020JCli...33.1487S. doi:10.1175/jcli-d-19-0075.1. ISSN 0894-8755. S2CID 210273007.

- ^ Yadav, Juhi; Kumar, Avinash; Mohan, Rahul (2020-05-21). "Dramatic decline of Arctic sea ice linked to global warming". Natural Hazards. 103 (2): 2617–2621. Bibcode:2020NatHa.103.2617Y. doi:10.1007/s11069-020-04064-y. ISSN 0921-030X. S2CID 218762126.

- ^ "Ice in the Arctic is melting even faster than scientists expected, study finds". NPR.org. Retrieved 2022-07-10.

- ^ Fisher, David; Zheng, James; Burgess, David; Zdanowicz, Christian; Kinnard, Christophe; Sharp, Martin; Bourgeois, Jocelyne (March 2012). "Recent melt rates of Canadian arctic ice caps are the highest in four millennia". Global and Planetary Change. 84: 3–7. Bibcode:2012GPC....84....3F. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2011.06.005.

- ^ J. C. Stroeve; T. Markus; L. Boisvert; J. Miller; A. Barrett (2014). "Changes in Arctic melt season and implications for sea ice loss". Geophysical Research Letters. 41 (4): 1216–1225. Bibcode:2014GeoRL..41.1216S. doi:10.1002/2013GL058951. S2CID 131673760.

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 Ch9 2021, p. 9-6, line 19

- ^ "Arctic summer sea ice second lowest on record: US researchers". phys.org. 21 September 2020.

- ^ Slater, T. S.; Lawrence, I. S.; Otosaka, I. N.; Shepherd, A.; Gourmelen, N.; Jakob, L.; Tepes, P.; Gilbert, L.; Nienow, P. (25 January 2021). "Review article: Earth's ice imbalance". The Cryosphere. 15 (1): 233–246. Bibcode:2021TCry...15..233S. doi:10.5194/tc-15-233-2021. hdl:20.500.11820/df343a4d-6b66-4eae-ac3f-f5a35bdeef04.

- ^ Francis, Jennifer A.; Vavrus, Stephen J. (2012-03-28). "Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid-latitudes". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (6). Bibcode:2012GeoRL..39.6801F. doi:10.1029/2012GL051000. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ^ Meier, W. N.; Stroeve, J. (April 11, 2022). "An Updated Assessment of the Changing Arctic Sea Ice Cover". Oceanography. 35 (3–4): 10–19. doi:10.5670/oceanog.2022.114.

- ^ Goldstone, H. (September 18, 2023). "Natural atmospheric cycle has been stalling the loss of Arctic sea ice". Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ Polyakov, Igor V.; Ingvaldsen, Randi B.; Pnyushkov, Andrey V.; Bhatt, Uma S.; Francis, Jennifer A.; Janout, Markus; Kwok, Ronald; Skagseth, Øystein (31 August 2023). "Fluctuating Atlantic inflows modulate Arctic atlantification". Science. 381 (6661): 972–979. Bibcode:2023Sci...381..972P. doi:10.1126/science.adh5158. hdl:11250/3104367. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 37651524. S2CID 261395802.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search